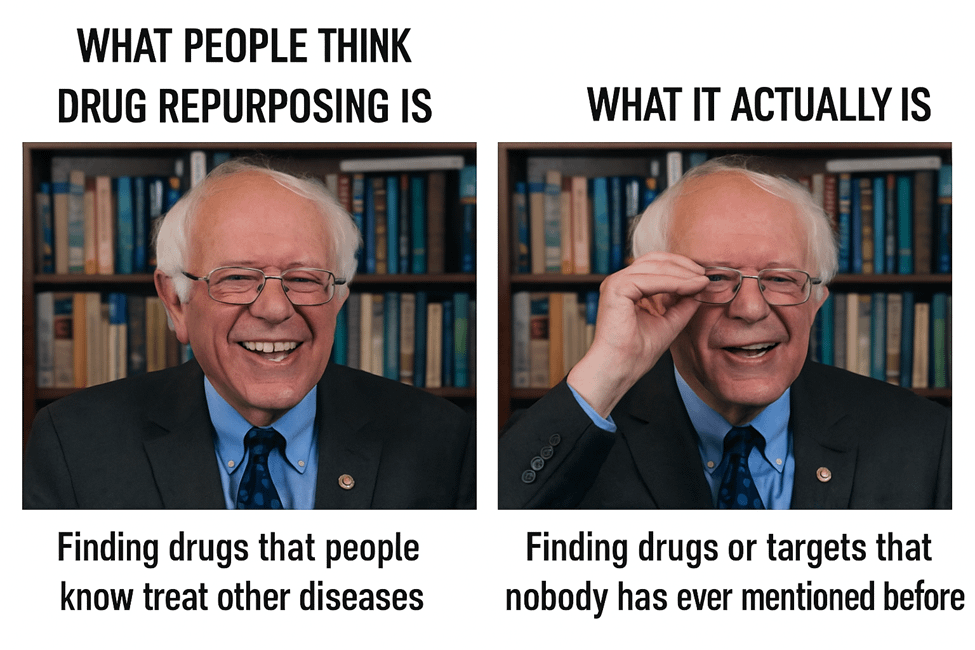

They often showcase how well a method can “rediscover” drug–disease links that already appear in the literature. That may look convincing, but it misses the real challenge: finding drug candidates that nobody has talked about before.

In a true repurposing or hypothesis-generation study, every prediction should be labeled as either:

1. Already known in the literature

2. Truly novel and never discussed

Only the second category matters scientifically. But identifying novelty is extremely difficult once the scale grows.

With a few predictions, manual PubMed searches work. With hundreds or thousands across many diseases, manual checks become impossible. Biomedical literature expands so quickly that no human team can reliably determine novelty.

To do this correctly, you must have structured access to all past biomedical knowledge. Without that, any analysis of novelty becomes guesswork. This is why we spent years building IKraph, a knowledge graph that converts the entire PubMed corpus plus many databases into structured form. It lets us check, at any time point, whether a drug–disease link has ever been mentioned.

Combined with our PSR algorithm and time-aware evaluation, we “go back in time,” use only the knowledge available at each year, generate predictions, and keep only those that were novel according to that year’s literature. Future publications, clinical trials, and database updates are then used to test whether those novel predictions eventually receive supporting evidence.

This removes information leakage, a major issue in many repurposing studies. Without controlling for novelty, methods can appear accurate simply because they predict relationships that were already known, even if those connections never appeared in the chosen benchmarking dataset. That gives an inflated sense of performance and makes fair comparison difficult.

Our recent study (Nature Machine Intelligence, 7, 602–614 (2025)) is, to my knowledge, the first large-scale repurposing study that rigorously distinguishes “already known” from “truly novel” predictions across the entire biomedical literature. This is not a cosmetic improvement. It changes how repurposing methods should be evaluated and how new hypotheses should be interpreted.

If drug repurposing is to mature as a scientific discipline, novelty detection must become a standard requirement. Repurposing is about uncovering the unknown. Without separating known from unknown, we cannot claim real discovery.

I hope more researchers adopt time-aware evaluation and comprehensive knowledge graphs. The goal is not to make models look impressive, but to find new therapeutic options for diseases with unmet needs.

What do you think? How should the field assess novelty at scale?

#DrugRepurposing #AIforDrugDiscovery #KnowledgeGraphs #BiomedicalAI #MachineLearning #DrugDevelopment